Connie Watts is a mixed media artist, whose work melds traditional west coast form and design with the complex modern world in which we live.

About

Connie Watts grew up in Campbell River. She is Nuu-Chah Nulth, Kwakwaka’wakw, and Gitxsan. She grew up as “the only brown face” at Evergreen Elementary School in Campbell River, with exposure to the images and traditions of her culture.

Her strong sense of form and design was shaped by her upbringing in a world of two cultures. This led to a pursuit of higher education in interior design at the University of Manitoba.

Everything changed abruptly when, soon after graduating in 1991 with a degree in interior design, Connie Watts was in a car crash that left her with memory loss and debilitating headaches. She moved to Los Angeles where she was able to get by with “a little less upstairs” but after two years she found herself unable to design, so in 1993 she came home to Vancouver and to Emily Carr University of Art.

Watts enrolled in Industrial Design, but her headaches returned and she switched into Intermedia. This is what Connie Watts calls “easing back” – while continuing to create fabulous native-referenced furniture pieces, she plunged into computer animation and 8mm film, drawing, painting, metal, wood, and fabric.

Fast-forward 25 years. Connie has healed through art. She has relearned to read and write while expressing strong views on coming to terms with colonization through her art and traditional teachings.

Watts is thrilled to be rediscovering her culture and reclaiming her own language through her art. The ancestral language of her grandmother, NuuChah-Nulth, was almost lost through a generation when “you got hit for speaking your own language.” Then, two years ago, her mother, Jane Watts Jones, took a teaching job at the Ha-Ho-Payuk School in Port Alberni, where children are learning the traditions and language of their ancestors. However, the Nuu-Chah-Nuith tongue is an oral tradition and the only written teaching aids were a handful of photocopied booklets transcribed into international phonetic symbols. “In her spare time,” Connie plunged into yet another medium, designing picture books to teach and reclaim the near-forgotten language. Working side by side with illustrators, teachers, and linguists, Watts completed Huksaa: The Nuu-Chah-Nulth Counting Book and the Nuu-Chah-Nulth Phonetic Alphabet. The books are bright and whimsical jewels, full of delicious illustrations enhanced by Watts’s razor-sharp-design sense and- her raven’s cheeky humour.

Her Work

Personal experience, familial relationship, issues of identity and language, the tension between modernity and cultural connection, and the search for authenticity influence Connie Watt’s work.

Vereinigung (German for “unification”) represented the culmination of Watts’s work at Emily Carr, “bringing together past and present, humans and animals, space and body, real and abstract kind of self-portrait, the figures represent f Watts’s character-the wolf a fiercely determined hunter, the bear strong and nurturing, a raven a clever trickster and lover of shiny objects. Each three-dimensional figure is built from layer upon layer of oiled plywood connected hundreds of small dowels-over 600 square home for humans surrounded and provided by animal protectors. Vereinigung turns in upon itself with meaning, ideas resonating in the spaces between the fragile layers.

Watts blurs the line between art and design, melding the aesthetic with the pragmatic. “Everything is a circle,” says Watts. “In school, I learned about ‘form and function’, the very Western approach, but when I turn back to my own culture, I use form to delineate space, then I circle back again … we used to have huge pieces of wood to carve out light and shadow, but now we use what is left plywood. We use what should be precious and beautiful for all the wrong reasons. In Port Alberni, they grind up trees to make plywood for row houses. So I use the plywood to make art … it’s all a veneer,” she laughs, savouring the pun. Quoted from Native Online

Commissioned work includes Hetux, a large Thunderbird sculpture composed of Baltic birch and powder-coated aluminum, intricately canvassed with animals, moons and sun representing the essence of her grandmother, installed at the Vancouver International Airport.

Her first outdoor work was “Kinship of Play” in the city of Parksville in 2010.

“Strength from Within”, was officially unveiled on Oct. 1, 2014.

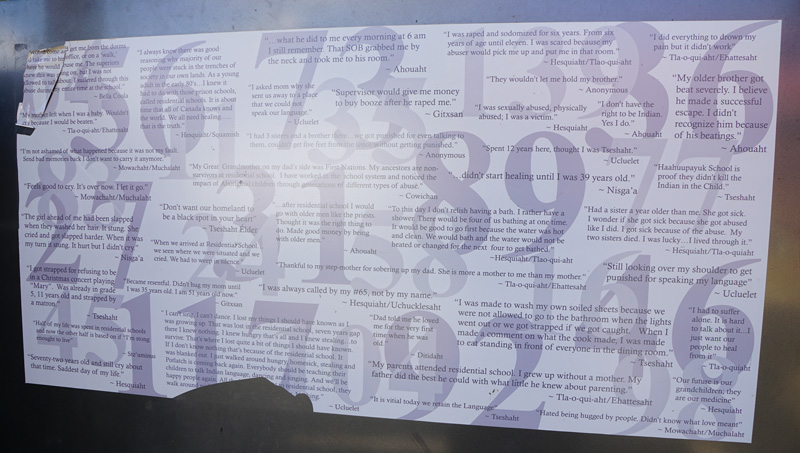

It stands next to the Tseshaht longhouse and on the site of the notorious former Alberni Indian Residential School. It will serve as a constant reminder to all of the horrors that occurred at AIRS over the decades, to honour all who didn’t return to their families and pay tribute to the resiliency of all those who survived their time there.

“It was the hardest thing I’ve ever done,” she said, her voice trembling with emotion. “How dare they call it a school,” she said. “It was a prison. There was no education.” It was “a concentration camp for kids.”

These days Connie Watts spends a lot of time on the ferry, shuttling back and forth between Vancouver and Port Alberni where she is working on two more language books. She is feeling stronger every day, her “head coming back,” energy radiating in all directions. For all this restless spirit, she has her grandma to thank, “who said ‘never stop dreaming!’ She is 83, and she still gets out there in the garden with the roto-tiller. That’s my West Coast upbringing, I can’t stop at one thing, I have to just keep on going!”

Her work has been shown in solo and group exhibitions in North America, most notably the Changing Hands: Art without Reservation 2 exhibition at the Museum of Arts & Design in New York, and her solo exhibit Re-Generation at the Urban Shaman Gallery, Winnipeg, Manitoba.

Connie has also collaborated with many other artists such as: Lori Wilson, Lawrence Lowe, Judy Farrow and Chris Doman.

For Connie, art is to give a voice and expression to her indigenous roots and not solely for monetary gain.

She has a separate business where she works as an interior designer in many areas, including a large executive office project that united her expertise in art with design.

In 2014, Connie completed the interior design for the Songhees Wellness Centre — a 48,000 square foot contemporary commercial building that fuses art, architecture, and design with the Songhees culture Centre.

Connie was the project manager for the Vancouver 2010 Olympic Committee’s Aboriginal Art Program. As curator on that project, she was responsible for the procurement, commissioning, execution and installation of over 50 artworks in the 16 official Olympic venues — an accomplishment marked by the publication of “O Siyam,” a book celebrating the Aboriginal Olympic artworks.

Connie is the newly appointed Associate Director of Indigenous Studies at Emily Carr University of Art.

Over the course of describing her extraordinary journey, and the ways in which her unique experiences as an artist, designer and educator interact with her perspectives as a woman of Nuu-chah-nulth, Gitxsan and Kwakwaka’wakw ancestry — gently illustrates that answer again and again.

Consider the process of reviewing an artwork, she offers.

“You’re not critiquing an object, you’re critiquing a living thing,” she says.

“And if it was a living being in front of you, you wouldn’t disrespect it. You would look and find what the strengths were, and how you could help build those strengths. You would learn to understand the piece through the life of it.”

The same goes for any learning situation, whether art or life, she adds. In acknowledging the fundamental equality between ourselves and the world around us, we find ourselves responsible to care for the world as we care for our own flesh and blood.

Applying such a worldview to the governance of spaces such as universities, businesses or professional relationships, she notes, is part of what decolonization is about.